Snap Hill from Aldbourne

- Distance: 5.1 km / 3.16 miles

- Average gradient: 2.3%

- Maximum gradient: 10.0%

- Elevation gain: 134 m

- Elevation change: 116 m

Snap Hill (climb 2)

from Ogbourne St George

Snap Hill

- Distance: 0.9 km / 0.54mi

- KOM VOM: 2,171 m/h

- Average gradient: 9.2%

- Maximum gradient: 16.6%

- Elevation gain: 80 m

Race Report 2014

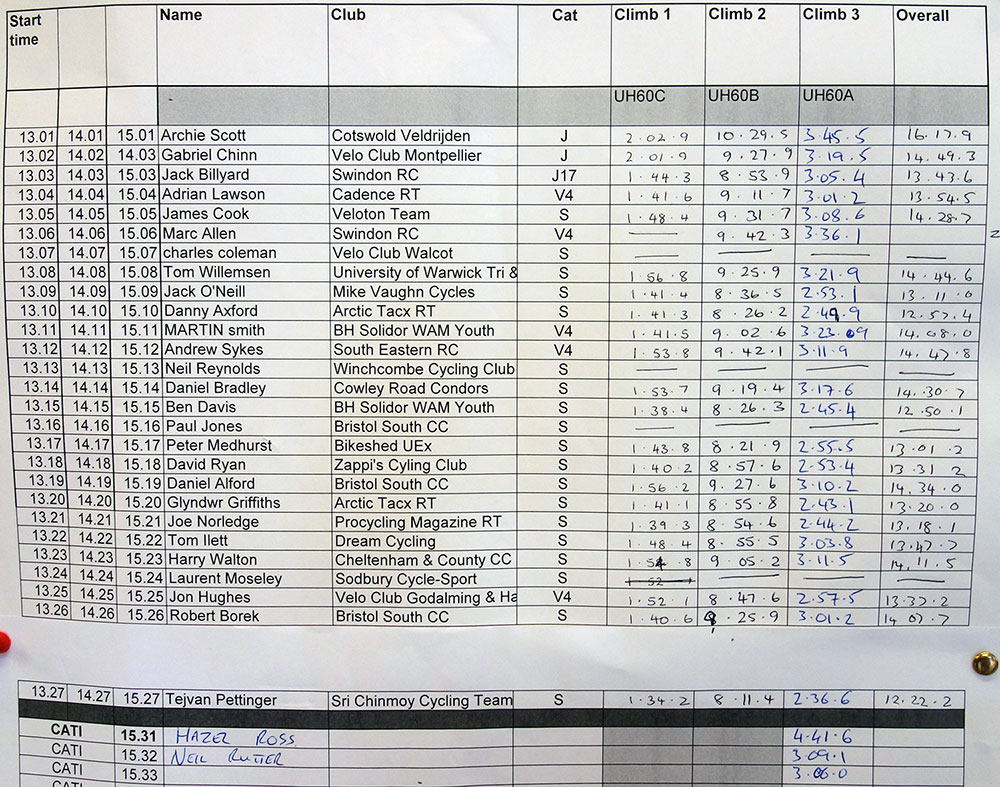

Sat 13th September was the Cotswold Veldrijden triple hill climb near the village of Aldbourne. It makes a change to have a local hill climb and not a long trek up the M6. Because it was local and early season I was quite relaxed. In the morning I got absorbed in writing an economics essay (on Scottish independence of all things) and suddenly realised I was well behind schedule. I ended up in a mad – pack everything up in 15 minutes kind of panic – which primarily involves throwing anything you see into a bag and hoping for the best.

Inevitably this speed packing meant forgetting several things. The most irritating thing to forget was my Garmin. After the race, I felt bereft at having no power meter file to look at.

Nevermind, I remembered my bike, shoes and wheels, which is the main thing you need to do a cycle race. It was such a nice late summer day, it was a little hard to imagine the hill climb season has really started. When the wind and rain return, maybe I’ll find it easier to get in the hill climb mindset.

It’s been quite a big week of training since the last hill climb at Buxton last week. Thursday I did several repetitions up Chinnor hill before watching the Tour of Britain go up the next day. I didn’t feel tired, but it’s been a lot of hill climb intervals in the legs this week.

The first climb was something of an unknown. It was the first time it had been used in competition and I don’t think anyone knew what to expect. I didn’t have time for a practise run, I just descended and thought this is quite short and not too steep. Even so, the finish still loomed quicker than expected. I managed an impressive sprint, but with still the feeling there was more in the tank – many other riders said the same thing. Next year, I recommend putting it in the big ring and sprinting from the start. I set a course record (by virtue of being first to win an event) in a time of 1.35 – but it’s definitely a course record for the taking.

An hour later was time for a different climb, a fairly steady (3%) climb from Aldbourne to Ogbourne St George. A little steep at the bottom, there is then a steady gradient before quite a fast downhill section near the finish. If it was the only hill, I might have bought my time trial bike. But, with a tailwind, I didn’t think it worth bringing. I rode the hill quite well and set a new course record of 8.11. I overtook my minute man – Robert Borek of the Bristol South CC who was gamely entering all three climbs on a fixed gear bike. I always admire people who ride fixed, even if I’m not so keen to emulate them. There were many other very good times with quite a few riders getting under 9 minutes and a few sub 8.30. It was a good day for that climb.

After two climbs you begin to feel a little fatigue and it was time for the last short, sharp shock up Snap Hill.

I was quite happy waiting at the top and watching some of the early riders finish the climb. It was nice to be a spectator in hill climbs for a change. The top of the hill offers great views over Malborough Downs.

There was a light headwind on the climb, which made it a little harder. It is also the most testing of the three climbs with a solid 16% gradient for much of the middle climb. Only towards the end does it level off, allowing a short sprint for those with anything left. I did 2.36 – 6 seconds slower than when I rode the hill two years ago – but that day was a tailwind and I used a TT bike.