Tapering is the art / science of trying to peak for a particular event. This can be a major taper, where you try to gain maximum performance for a major race (usually once or twice a year) There are also minor tapers, where you try a shorter taper for races of medium importance throughout the year.

The basic principle of tapering is that there are two main aspects of training:

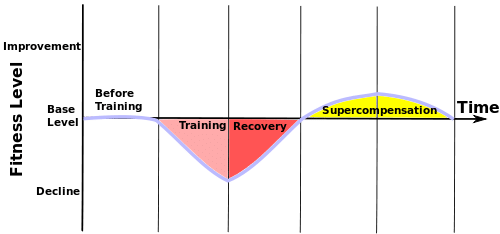

- Stress – where you do the training and stress the muscles and body. This leaves fatigue and possible muscle damage, but the stress causes the body to adapt to higher levels of fitness. Without this stress, the body never tries to adapt to greater fitness.

- Recovery – where you rest and give time for muscles to recover and adapt to higher levels of fitness.

The idea of a taper is to gain the optimal amount of fitness, plus freshness. If you train too hard, you will enter the final competition too fatigued and unrecovered. If you rest too much, then you start to lose the fitness gains. The peak taper is to get best combination of fitness, plus freshness.

Generally tapering involves reducing the volume of training, but maintaining a similar number of sessions of the same high intensity. This reduction in training volume can be anything between 5-21 days.

Some people racing every week may do a mini weekly taper of reducing training towards the end of the week. But, I wouldn’t really call this a proper taper.

Out of interest, in 1954 Roger Banister, took 6 days off before his successful attempt to be first man to run the mile under 4 minutes (3 min 59.4 sec) (link)

Benefits of Tapers

Different studies, suggest that a taper which reduces fatigue from an endurance athlete can boost performance by between 3-11%.

- VO2 max capacity is largely unaffected by taper.

- Hemoglobin blood values have been shown to increase by up to 14%

- Hematocrit values have been shown to increase by up to 2.6% (Correspondingly at the end of a long tour, blood values are expected to fall. Hence athletes which show rising Hemotcrit levels at the end of a three week tour, is a strong indication of blood doping)

- One of the biggest increases in capacity after a taper is in sport specific muscles. Increases in swimming-specific power, of 16–25% have been reported in both men and women (9, 53)

How to develop a taper

A taper will depend on several factors. Firstly, it depends on how much you are training. If you are training less than four hours per week, a taper is unlikely to have any benefit, because at the level of training, fatigue is unlikely to be an issue. The greater the training volume, the greater the accumulated fatigue and the greater potential benefit of a taper.

One suggested rule of thumb:

- 6-10 hours training – major taper – 7 days

- 10-15 hours training – 14 days

- 15+ hours – 21-30 days