I was chatting to some ‘non-cyclists’ interested in trying to understand why breakaways nearly always get caught a few km from the finish. I thought it would be a quick and simple thing to explain, but I ended up writing a lot.

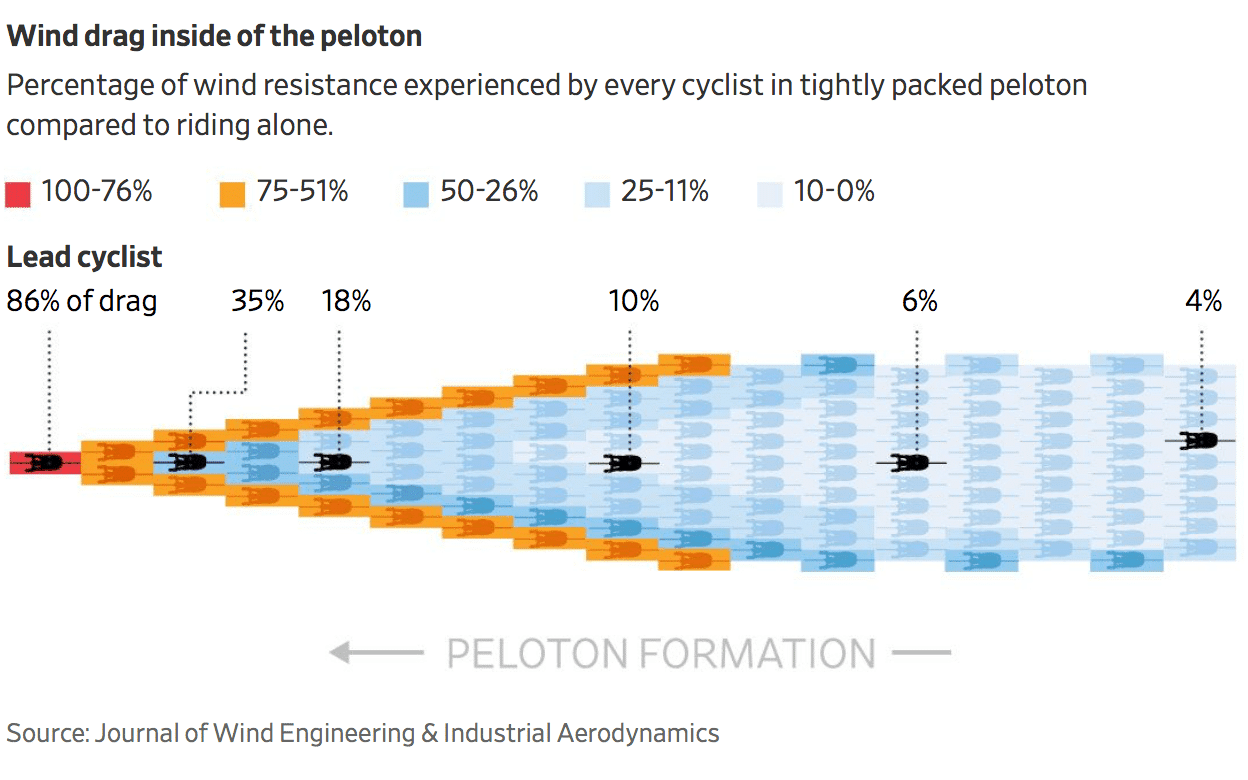

In cycling, the biggest drag on effort is aerodynamics (up to 90% of drag when travelling at 50km/h). Therefore, you save considerable energy riding in the middle of the peloton. One study suggested that riding in the middle of the peloton can mean you only need 5% of the energy you would if you rode alone. You can be doing 50 km/h, but the effort is similar to 12 km/h. If you ride in the peloton all day, you can get to the last 10 km relatively fresh and ready to make a big effort.

If you ride in a small breakaway, you are making much more effort throughout the day, you will get some drafting benefit, but you will have to ride with your nose in the front for considerably more. When you get to the last 10km – the breakaway riders will be closer to exhaustion than the riders in the peloton. Then in the last 10km, there are fresh riders ready to chase down the breakaway and set up a sprint.

There will usually be many teams with a motivation to chase down the breakaway. The best sprinters will have a team willing to ride and bring back the breakaway. If a team doesn’t have someone in the breakaway, they might as well contribute to bringing back the breakaway – otherwise, they will have no chance of winning.

Secondly, if it is a one day race like the World Championships, the best riders will tend not go in the breakaway. Therefore, it becomes self-fulfilling, weaker riders enter the breakaway – either for tactical reasons or perhaps just to get some tv exposure.

A breakaway would have more chance of winning if there were more people in the breakaway and stronger riders were in it. But, at the start of the race, teams will be looking to control who gets in the breakaway. If a strong favourite tried to sneak into the breakaway, the peloton may chase down the breakaway and bring the favourite back – rather than let the break get established.

A more interesting question is what enables a breakaway to succeed?

What enables a breakaway to succeed?

Miscalculation. Teams may use a rough rule of thumb. For example, a fast-moving peloton may feel that it can bring back 1.30 for every 10km. If there are 20km to go, and the breakaway has a gap of 3.00 – it is touch and go, so they may start making more of an effort to bring it back. However, it may be that the peloton miscalculate the strength of the breakaway and leave it too late.

If everyone waits for someone else to do it. Sprint teams wait for others to take the responsibility to bring it back. If a team of a sprinter works all day to bring back the breakaway – they may have no energy left to set up their sprinter – so they may try to do as little as work as possible during the day – let other teams do the hard work of chasing the breakaway and then be strong in the final 5km. However, if all teams try to get others to work, it can lead to a breakdown in co-operation. All sprint teams are in effect playing ‘chicken’ – seeing if others will crack and be the ones to do the work. There is an unwritten law in the peloton that if you want to be prominent in the sprint, you should at least put one rider at the front of the peloton to help bring back the breakaway. But, sometimes the co-operation of the sprint teams breaksdown and then the breakaway succeeds.

Careful pacing by breakaways. If a peloton is catching a breakaway too quickly – it will sometimes slow down so it doesn’t catch the breakaway too early. This may sound strange, but if you caught a breakaway with 50km to go – it would encourage a second breakaway – and therefore require even more effort. The ideal plan is to catch a breakaway in the last 5km. – Don’t expend more energy than you need. The breakaway can use this to their advantage. Go relatively easy for the first 200km – hoping the peloton will back off – giving them the same gap and then in the last 20km – lift the effort so the breakaway is much stronger than the peloton expected. It is like when Harry Tanfield (riding for Canyon Eisberg) a small UK Pro-Conti team) won Stage one of the Tour of Yorkshire (2018). The peloton probably expected to catch – but Tanfield was very strong on the flat and just held off the peloton.

Small teams. When the Tour de France was nine-man teams, a top sprinter like Mark Cavendish could have eight riders devoted to bringing back a breakaway and setting him up for the sprint. Breakaways are rarely bigger than eight riders so in effect one sprint team should be stronger than the breakaway – and in practise, several teams will contribute. But, in a smaller race like the Tour de Yorkshire, teams don’t have the strength in depth so there isn’t the same dominance of a team to chase down a breakaway. When Mark Cavendish won the World Race Championship in 2011, GB had a team of nine riders to spend all day chasing down the breakaway. They timed it to perfection. At the 2012 Olympics, they tried to repeat their tactics, but this time with a team of five people. It didn’t work.

Everyone lent on Great Britain to do the chasing, but they ran out of steam and the 4 GB riders couldn’t bring back a breakaway of 10-12 riders. It was also a disadvantage for GB to be such strong favourites – no-one else wanted to chase the breakaway because they felt Cavendish would win the sprint – ironically having such a strong sprinter tilted the balance towards the breakaway. Other countries thought – we don’t want a sprint, so we might as well try a breakaway (which went away quite late on Box Hill.)

Middle of a Grand Tour. In a prestigious one day race like the Tour of Flanders, early breakaways ver rarely succeed. Everyone is 100% motivated to ride for their team leader. However, in the middle of a Grand Tour like the Vuelta Espagne teams are tired, and many riders are concerned with GC (General classification) If Chris Froome is in the yellow jersey and a large breakaway goes up the road, then his team will not work too hard. They are quite happy for the breakaway to win the stage – it makes life easier for them. If the stage is a little hilly, sprinter teams may not bother working all day to chase – as they are not sure their sprinter will make it. So there is no-one to chase breakaway really hard – so many teams think breakaway is the best bet of winning the stage – so if fifteen teams have a rider in the breakaway – there’s no one left to chase it down.

Medium hilly stages. If a stage is flat – like the final stage on the Champs Elysees, everyone knows the sprinting teams will be fully committed to chasing the breakaway down. Therefore, the chances of a breakaway staying out are extremely slim – it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. But, if the stage is quite hilly – and with twisty and windy roads, it makes it easier for a breakaway to succeed as sprinters teams will not be so motivated. In stage 4 of the 2018 Tour de Yorkshire, a breakaway went at the start of a very hilly stage. It was so hilly, teams were very conservative in riding, so they allowed a small breakaway to get 10 minutes by the foot of Park Rash, then Stephane Rossetto (Cofidis) rode away to win a very rare kind of all day breakaway – the reason was that teams were happy to let him go so early. They didn’t want to ride too fast at the start of such a hilly and difficult stage.

Unexpected weather. If there are strong cross winds, the peloton is likely to split up as riders ride in echelons to get protection from sidewind. A peloton split up into small parts is more likely to see breakthrough win. If there is a strong tailwind for the last 10km – this benefits the breakaway. The benefits of drafting in the peloton is less when there is a tailwind. It is often a strong headwind that kills the chances of a small breakaway.

Get lucky In 2016, Matthew Hayman won from a breakaway in Paris-Roubaix after leading riders (and pre-race favourites) caught up with the breakaway and no-one was really looking at Hayman in the five-man sprint. In 1988, a breakaway also won Paris Roubaix when relatively unknown rider Dirk Demol won. Demol was only a domestique (who had to ask his Director Sportive to pick him). But, somehow the peloton misjudged, Demol benefitted from the hugely powerful Thomas Wegmuller driving the breakaway and then Demol won a two-up sprint against Wegmuller – there is a good account of race here.

Breakaway specialists. In Grand Tours, everyone has different objectives. Several teams will be concentrating on the overall; some riders could solely to try and win a stage. Breakaway specialists include riders like Stephen Cummings (GB) and Thomas De Gendt (BEL). These are very strong powerful riders, who could, in theory, be contenders for the overall. However, for various reasons, they prefer the role of seeking individual stages – rather than the more pressured role of fighting for the GC – which means riding at the front of the peloton and watching your position for the entire three weeks. A breakaway specialist like Cummings often rides at the back of the peloton – the least stressful place – it means if there is a crash, he could lose time on GC but they don’t mind. In fact, if they lose time, it makes it easier to get in a breakaway as they are not considered a threat. In stage 8 of the 2019 tour, Thomas De Gendt was in a breakaway until the last 10km – when he simply rode away from the breakaway and held off the peloton. Very few riders could have done what he had done – he displayed the power of a GC winner. The breakaway was unexpectedly strong.

A very big breakaway – big breakaways can happen in grand tours when GC teams are happy to let people go stage hunting. This means you can ride in the breakaway and do very little work. Teams may have three riders in the breakaway – they will then choose one rider to do no work but sit on the back of the breakaway – then in the last 10-20km, the protected breakaway rider is fresh to make big effort. In a big one day race, the peloton wouldn’t allow a big breakaway – it would be chased down.

Type of roads. If you have flat wide open roads – it favours the fast-moving peloton. However, if the roads are twisty and windy, it favours smaller breakaways. This is due to the ‘whiplash effect. When you go round a narrow corner the peloton loses its momentum; if you are riding 30th wheel you have to really slow down and then accelerate around a corner. It is easier to manoeuvre a small group of 4 than a group of 100.

Slower speeds. If you are racing on a slow road surface – often called ‘grippy’ or cobbled roads, then the benefits of drafting are less and it slightly favours breakaways and less so the peloton. Aerodynamic drag increases exponentially with speed. If you are travelling at 40km/h – there is a benefit to being in the peloton. But, if it is going at 50km/ – the benefits is substantially more than 50km/h.

Do breakaways ever win the World Championships?

The World Championships are rarely won by the breakaway. The strongest riders save themselves for the final stages and rely on team mates to control the breakaway.

Recent article on this in the Journal of Economic Psychology. Socio-economics and game theory – a slightly different perspective from the usual sports science.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167487017307596

Why is the peloton told how far ahead the breakaway is?

After all it is a race & why should the majority be allowed to take advantage of the effort the breakaway make.

Which other physically powered race do you tell the other competitors how far they are behind?

no other sport does this simply because its not necessary. for example you have running in track and theres no point in them holding a gps tracker with them or a device in their ear for the team to radio simply cos they can just look up at the screen to know how far back their opponents are. every sport has knowledge of others in the race just in different ways. also the breakaway know how far the peloton is so its fair game for all.