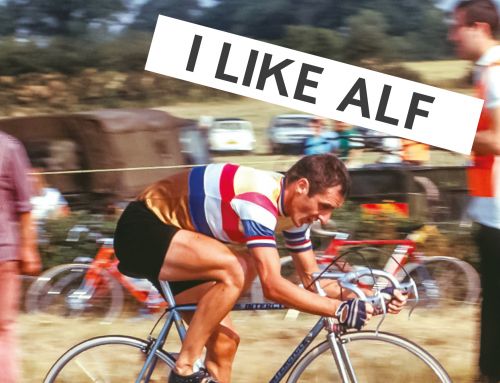

You can’t do time trialling in the UK without becoming dimly aware of a mythical figure called Alf Engers. Emerging out of that ‘golden age’ of the 60s and 70s when timetrials ruled the road, you pick up the odd snatched comments about the first sub-50 minute 25 mile TT on a road bike (no TT bars). Riding in the middle of the road. Brushes with authority. The London baker doing a night-shift to 3 am and then breaking records at 6 am. Even now, as the author mentions, you can still hear the phrase “But, what would Alf Engers have done?”

You can’t do time trialling in the UK without becoming dimly aware of a mythical figure called Alf Engers. Emerging out of that ‘golden age’ of the 60s and 70s when timetrials ruled the road, you pick up the odd snatched comments about the first sub-50 minute 25 mile TT on a road bike (no TT bars). Riding in the middle of the road. Brushes with authority. The London baker doing a night-shift to 3 am and then breaking records at 6 am. Even now, as the author mentions, you can still hear the phrase “But, what would Alf Engers have done?”

It all amounts to whispers from the past and, in the absence of direct testimony, you place your subjective impressions above any reality. Muffled opinions in between the course codes and obscure regulations. The funny thing is whenever I met the late John Woodburn, he would always tell me how he had to start a time trial with a working bell, and when he got around the corner from the start-keeper, he would throw it off in disgust. It’s a shame I never asked about his times racing with Alf Engers. It never occurred to me, but that’s one of the many things I learnt from the book.

The thing about legends of the past is that you never quite know fact from fiction, exaggeration from reality. Timetrialling doesn’t tend to throw up too many characters; it’s a sport for the nerds and obsessive attention to detail. A rock star in a sheepskin coat who snubbed his nose up at the stuffy RTTC by riding too fast has all the makings of a great story.

When I heard Paul Jones would be writing a book on Alf Engers, I thought somehow that this was a match made in Heaven. If ever a writer could do justice to a biopic of ‘The King’, it was P. Jones – who can make even sparsely populated hill climbs sound exotic and exciting. Except with Alf – ‘Heaven‘ is perhaps not quite the right epitaph; more like a “match made in Heaven – with a touch of the devil’s mischief thrown in for good measure.”

If there is a drawback to the book, it is short. I read in two days. But, it reminds me of the pastor who gave an interminably long sermon of two hours – and when asked why his sermon was so long, he responded that he didn’t have time to make it short. Brevity is the soul of wit and all that. The benefit is that the book moves along at a great pace, evoking the spirit of the times from post-war Britain to the slow evolution of parochial time-trialling. At last, I have a direct understanding of Engers. – What made him tick, what he did for the sport, the great battles of the past – all within the context of today. It was like finding out that Robin Hood is a real historical figure, and he was a pretty decent bloke to boot.

As a story, you couldn’t make it up. It is hard to understand why a full-time baker could be banned from the sport for five years (age 22-27), because he had one failed season as an independent. It seems the spirit of amateur endeavour were lost in the rules, regulations and prejudices of the time. It is Alf’s comeback which is really the riveting part of the book. National records, complaints, counter-complaints, detractors and supporters in equal measure – it is all told with great pace, humour and sympathy to the rider who was breaking both records and pulling the RTTC out of its carefully controlled past.