Time trials are the simplest aspect of cycling sport. Riders go off at timed intervals and race alone. The fastest rider wins. It is a simple race against the clock or as they say in France – ‘contre la montre’

It has also been called ‘The Race of Truth’ because there are no team tactics. The strongest rider should win.

It’s not as exciting or spectacular as road races, but, time trials are often included in big stage races like the Tour de France and can be exciting in their own right for big events. It is often the time trial which decides who wins the big Tours. For example, in the 1989 Tour de France, Greg Lemond (USA) famously overturned a 50 second deficit on the final time trial to win the Tour by 8 seconds.

Rules of Time Trials

The rules of time trials are fairly simple.

- Ride the course

- Don’t take shelter from other riders (known as drafting)

- Have a bike fitting regulations of the cycling body.

In practise, there are many minor rules. The UCI have very strict rules about the placing of your saddle, angle of handlebars and even the aspect ratio of materials. In the post war period, the UK Road Time Trials Council (RTTC) had a long book of rules, including having a bell on your bicycle.

History of Time Trials

In the 1880s, UK mass start road races were constantly under attack from the police. This was due to complaints from (the generally wealthy) motorists that felt they were being terrorised by ‘furiously fast cyclists’. This was in the day of motorists driving at 10mph (how times have changed…)

An early time trial. The rider is performing a ‘dead-turn’ – a u-turn in the middle of the road. He is also dressed all in black. It is rather quaint that there was a time when you can stand in the middle of the road as the turning point for a cycle race.

Due to the precarious nature of cycle races in 1890, The British Cycling Union, wanted cyclists to only race on velodromes and not on roads.

However, there were rebels. Led by Fred Bidlake, some cyclists formed secret cycle races, which they hoped wouldn’t attract the attention of the police.

- The races involved people starting at one minute intervals.

- Riders wore all black. These were hoped to be the most inconspicuous clothes. Even as late as the 1930s, riders could get disqualified for not having black socks.

- Races were often early morning

- Legend has it the courses were given secret codes, known only to the racing fraternity, like the H25/14 – codes which still apply today.

- If a rider in a time trial was stopped, he could just say he was out for a cycle and not part of a race.

In the UK, time trials become very popular, helped by the growth of cycling as a popular means of transport and sport. Even when road races were later legalised on UK roads, time trials had become deeply embedded in British cycling culture.

On the continent, big road races were organised – like Paris-Roubaix, Milan San Remo and the Grand Tours. These big road races proved commercially very attractive, but back in the UK time trials maintained a very strict low key, amateur approach. In the post war period, the dominance of time trials in UK cycling has often been put forward as to why the UK didn’t have any good pro-cyclists (until 2000s and 2010s)

In the post war period, there was often friction between Road Time Trials council and the League of British Racing Cyclists. The RTTC opposed the reintroduction of road races and banned people from their events if they participated in the ‘breakaway’ union. Thankfully, these divisions are long since ignored, but there is still a split with some riders preferring time trials to road races.

Types of Time Trials

Chris Boardman on TT superbike

Chris Boardman on TT superbike

1. Prologue Time Trial. This is a short time trial. Usually ridden at the start of a major tour, like the Tour de France. They are usually less than 10 km. Britain’s Chris Boardman used to hold the record for the fastest ever Prologue in the Tour de France – riding at 55 km/h in the 1994 Tour de France. It was beaten by Rohan Denis in 2015, when he averaged 55.446kmh for the opening stage.

2. Fixed distances. In the UK, specific distances are very popular. These time trials are often held on flatish roads to help cyclists get the quickest times. (In fact some courses start at the top of a hill and finish at the bottom, so you get a net descent for faster times. The most common distances include:

- 10 Miles – record 17.20 Alex Dowsett (Movistar) 01/06/2014

- 25 Miles – record 45-54 Matt Bottrill 45.43 R25/3L 07/09/14

- 50 Miles – record 1.35.27 Matt Bottrill 1.34.43 (2014) A50/6

- 100 Miles – record Kevin Dawson – 3.22.45 (2003). There was a 3.18 100 mile TT, ridden by Richard Bideau, but the course was later measured to be slightly short, so it couldn’t stand.

3. Non Standard Distances. Time trials can be held over any difference. In major stage races, they are not usually concerned about a fixed distance and it could be anything from 35Km to 50Km. These courses may be held over hillier courses. The Olympic time trial is held over a distance of around 44Km for men and 29Km for the women.

Bradley Wiggins Time Trial

Bradley Wiggins winning Olympic gold 2012. photo Dept of Culture and media Sport

Bradley Wiggins winning Olympic gold 2012. photo Dept of Culture and media Sport

4. Distance Events 12 Hours 24 Hours. In the UK, there are also time trials held for certain periods of time. In these time trials riders cycle for as long as they can in the allotted time. The record for 12 hours is around – 317.912 miles Andy Wilkinson (2012). For 24 hours around 541.17 miles (2011) – Andy Wilkinson.

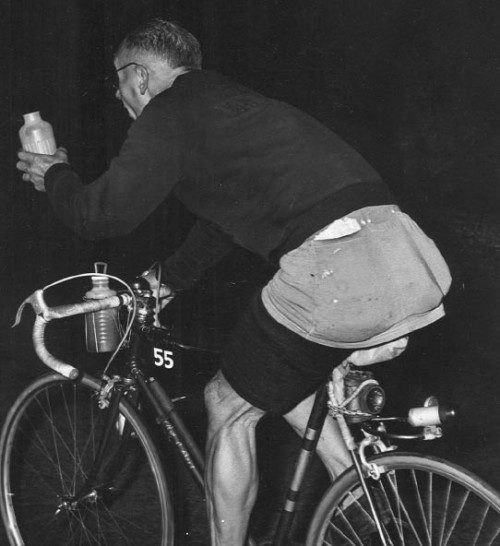

A 24 hour race during the night.

A 24 hour race during the night.

5. Hill Climb. A time trial which only involves racing up a hill. Riders still set off at one minute intervals. But the course involves riding straight up a hill. These can be from 1 km to 20+ km.

A hill climb – Catford CC – the world’s oldest cycle race.

How To Ride a Time Trial

Pacing. One of the main skills in riding a time trial is good pacing. The general idea is to be able to maintain the highest effort for the duration of the course. If a rider starts off too quick, he may end up being slower overall. A good time triallist will know how fast he can go for the required distance. Many beginners tend to set off too fast and fade towards the end.

Pacing into wind / hill. Although in a time trial, we try to maintain effort level over the whole course, this doesn’t mean you should try to put out the same power all the way around. It can be more effective to put in more power (effort) when going up hill and into a headwind. When you go downhill with tailwind, you can maintain high speed with relatively lower power. Aerodrag increases more than proportionally as speed increases.

Technical Aspects. Time trial bikes are generally harder to steer. (heavier, narrow tri bars). Therefore, racing on technical courses (course with many sharp turns) can require considerable technical skill. Even in big pro time trials, you may often see riders overcook a corner and fall off.

Training for a Time Trial

Time trials are endurance events so they require a good basic aerobic fitness. Then a rider needs to increase their capacity to ride at high intensity – near their threshold level.

See also:

What is a good average speed for time trials?

For many years, the magic mark was to average 25 mph in a time trial. The first sub hour 25 mile TT occured in the 1930s. The first sub four 100 tt was achieved by Ray Booty in the 1950s.

In this period of fixed gears, heavy bikes and low traffic, many club riders would aim to break ‘evens’ – an average speed of 20mph +. In the early days of time trials, long distances were more popular – 100 miles, 12 hours were more common.

A BBAR Certificate was given to every rider who could average more than 22 mph for the combined distances of 50 miles, 100 miles, and 12 hours.

Times for time trials can vary depending on

- profile of course

- bike used

- Traffic assistance.

For example, if I rode a fast course on a time trial bike, with passing traffic, I have averaged over 30mph / 48 km/h for a 25 mile time trial. If I rode a road bike on a course with no passing traffic, the same effort may have given an average speed of 25 mph / 40 km/h.

Time Trial Bikes

Eileen Sheriden on an early fixed gear TT bike

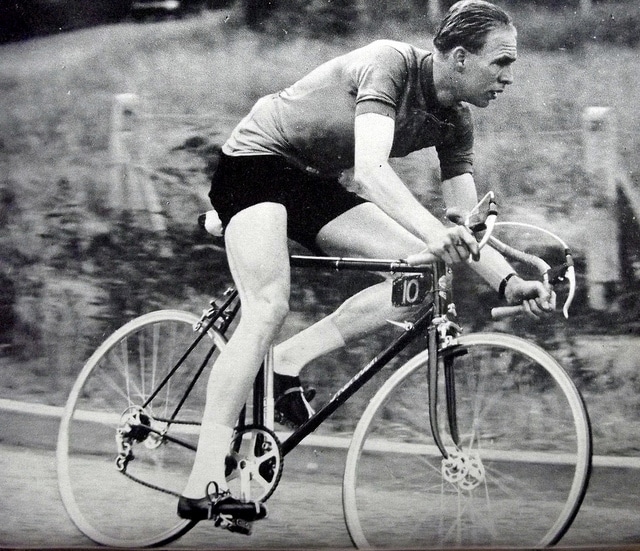

Frank Colden on an early geared bike

For many decades bikes used in time trials were pretty much the same as used in other road races. The first big strides in aerodynamics took place in the 1980s. Firstly Francesco Moser smashed Eddy Merckx’s iconic hour record by using disc wheels (Moser also admitted to blood doping as well) Moser set 50.8 Km in 1984. Merckx set 49.4Km in 1972

Greg Lemond Tour de France final 1989 time trial. Lemond won the Tour by 8 sec – Next year quite a few more riders were using tribars

Aerobars. The next huge step was the adaption of tri bars – so used because they were first used in triathlons. By bringing the arms closer together, they saved precious seconds.

By the mid 1990s, time trial bikes came in all kinds of exotic shapes and designs. For example, Chris Boardman’s famous Lotus Bike, which helped him to Olympic Gold in 1992.

The UCI were worried bike technology was getting out of hand, therefore they introduced stricter rules to keep designs limited.

Now time trial bikes are still very specific. They are designed and tested in wind tunnels, riders will spend hours checking their position and seeing what aerodynamic drag they create.

Aerodynamics and marginal gain

Even after the introduction of tribars, skinsuits and specific time trial bikes, recent years have seen remarkable improvements in speed due to better understanding of aerodynamics. Riders who spend time in wind tunnels can find even marginal changes to position and clothing can make very significant differences to the average speed they can maintain. A professional preparing for a time trial, will examine every possibility. For example, British Cycling had a secret ‘squirrel’ unit looking at every possible marginal gain – this involved specially designed skinsuits, which were performing much better than ‘ordinary’ skinsuits. Bradley Wiggins even shaved his beard off for his successful World Hour Record.

See: Aerodynamic gains for time trials

Some Famous Time Triallists

Beryl Burton – Dominated Women’s British Time Trials for decades. Once held a 12 hour time trial record which was greater than the mens record. She won the womens BBAR for 25 consecutive years.

Alf Engers

Jacque Anquetil. Dominated the Tour de France by excelling in time trials

Eddy Merckx – not really considered a time triallist because he was so good at everything. But, he still usually beat everyone in time trials. He also broke the World Hour Record – despite setting off at a ridiculous pace to try and break the 4km record along the way.

Miguel Indurain – In his prime almost untouchable in time trials. In one stage of the Tour de France, Indurain took six minutes out of his nearest rival in a time trial.

Graeme Obree

Graeme Obree – a unique British rider who broke world hour record twice – on his own invented bikes.

Chris Boardman – Also set three world hour records including a mammoth 56.3 km in 1993. (Now r

Bradley Wiggins – 2012 Olympic time trial champion, 2014 World time trial champion.

World Hour record holder 54km (2015). Once held the UK record for 10 miles

UK Time Trial Competitions

BBAR – A British event known as the Best British All Rounder Competition. It is a competition over 50 miles, 100 miles, and 12 hours. The rider picks his fastest rides of the season, and this average speed is compared against other riders. The BBAR was founded in the 1930s as a way to have domestic competition against riders who lived in different parts of the country. It was a very popular backbone of the British cycling scene during the 1950s and 1960s, with Cycling doing big spreads of BBAR tables. However, as traffic volumes increases in the 1960s, it encouraged riders to start to race on the busiest roads like the A1 and A50 to get faster times. Many think this makes competition flawed, but it has survived in its flawed state for many years now.

RTTC classic series. A competition on more sporting courses, where only position is counted, not time.

UK Time Trial Culture

In the UK, there is a strong time trial culture. On the continent riders may enter stage races with very little experience of time trials. But, in the UK, time trials almost is a separate sport with its own organising body – Cycling Time Trials.

The traditional aspects of British Time trial culture include:

- Racing early on Sunday morning (when traffic is light enough to race on very busy roads) – sounds bizarre I know.

- Cup of tea in exchange for your number

- Meeting in village halls and getting changed out of the back of your car.

- Races dominated by veteran riders (people over 40 years old)

- Riders get chance to try and beat their previous personal bests. Position in races are not so important. Often riders will be most pleased by fast times rather than high positions. (or these days pleased by high power figures)

Time Trial Terms

Not sure of the term for a time triallist riding a tricycle and smoking a pipe at the same time.

- Float day – a very fast day – good conditions – where many riders set a new pb

- Dead conditions. Riders may say the road was dead i.e. no passing traffic and rough surface making them go slower than if they had a smooth road.

- pb – Personal best – the elusive goal of time triallists.

- A Catch – overtaking rider who started a minute in front of you.

- Minute man – the rider who starts a minute before you.

- Tester – cyclist who rides predominantly time trials

- Negative split – riding second half of time trial faster than first half.

Related

- Classic time trial photos – the glorious b/w era – don’t miss, they are great.

- Cycling Time Trials

- 12 Champions

- see: Time trial Records

Another brilliant blog. I really do enjoy reading what you have to say about cycling and its surrounding elements.

I have been time trialing now for 2 full seasons now and I am getting my field tests down to 22.13. On the road is a different matter…..

I used to have a good coach, but expense sadly has put a stop to that. I train 4/5 days per week, mixing interval, long rides and continued testing. Could you suggest anything else i could be doing? Many Thanks and keep up the great work 🙂

Hi Daniel,

Glad you like blog. Sorry, it’s hard to give any training advice more than what I write on various blogs.

Thank you for the reply. I know that its difficult to “add” more detail. I will re read your various training pages and the 10’s of books that I have bought. It’s hard though to see the wood for the trees! Information overload…..Many Thanks